Like basketball scouts discovering a nimble, super-tall teenager, astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope reported recently that they had identified a small, captivating group of baby galaxies near the dawn of time. These galaxies, the scientists say, could well grow into one of the biggest conglomerations of mass in the universe, a vast cluster of thousands of galaxies and trillions of stars.

The seven galaxies they identified date to a moment 13 billion years ago, just 650 million years after the Big Bang.

“This could indeed have been the most massive system in the entire universe at the time,” said Takahiro Morishita, an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology’s Infrared Processing and Analysis Center. He described the proto-cluster as the most distant and thus earliest such entity yet observed. Dr. Morishita was the lead author of a report on the discovery, which was published on Monday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The scientists’ report is an outgrowth of a larger effort known as the Grism Lens-Amplified Survey from Space, organized by Tommaso Treu, an astronomer at the University of California, Los Angeles, to harvest early science results from the Webb telescope.

The telescope was launched into orbit around the sun on Christmas Day in 2021. With its infrared detectors and a booming primary mirror 21 feet wide, it is ideal for investigating the early years of the universe. As the universe expands, galaxies that are so distant in space and time are racing away from Earth so fast that most of their visible light, and the information about them, has been stretched into invisible infrared wavelengths, like receding sirens lowering in pitch.

In its first year, the Webb has already recovered a bounty of bright galaxies and big black holes that formed only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

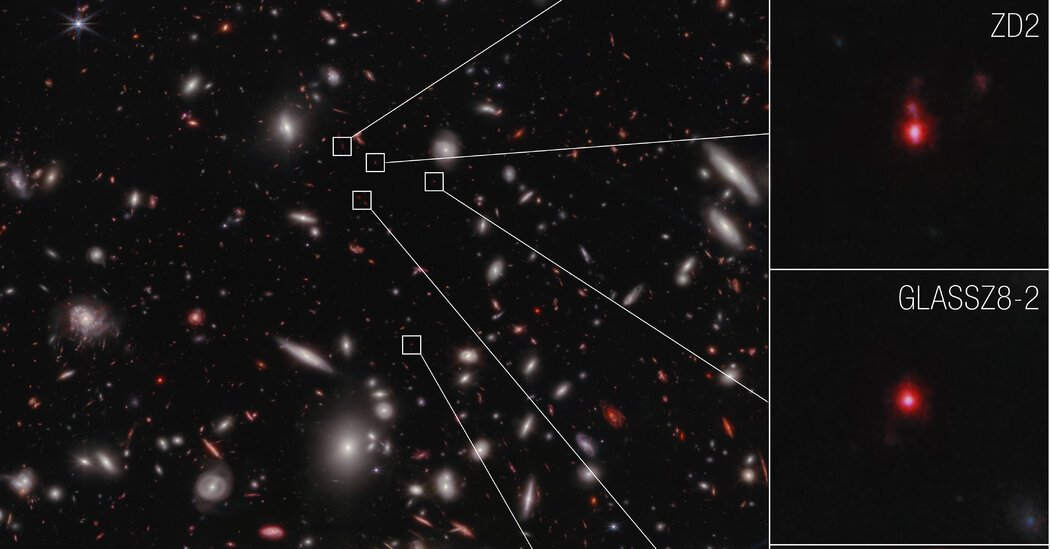

The latest infant galaxies had been detected over the years by the Hubble Space Telescope as red dots of light, visible at such great remove only because they had been magnified by the space-warping gravity of Pandora’s Cluster, an intervening cluster of galaxies in the constellation Sculptor.

Spectroscopic measurements with the Webb telescope confirmed that the seven dots were galaxies and were all equally far from Earth. They occupy a region of space 400,000 light-years across, or about one-sixth the distance from here to the Milky Way galaxy’s nearest cousin, the great spiral galaxy Andromeda.

“So, our efforts of following up on the formerly known potential proto-cluster finally paid off after almost 10 years!” Dr. Morishita wrote.

According to calculations based on prevailing models of the universe, gravity will eventually draw these galaxies together into a massive cluster containing at least a trillion stars. “We can see these distant galaxies like small drops of water in different rivers, and we can see that eventually they will all become part of one big, mighty river,” said Benedetta Vulcani of the National Institute of Astrophysics in Italy and a member of the research group.

The spectroscopic data also allowed Dr. Morishita and his colleagues to determine that the stars populating some of these embryonic galaxies were surprisingly mature, containing sizable amounts of elements like oxygen and iron, which would have had to have been forged in the nuclear furnaces of generations of earlier stars. Others among the infant galaxies were more pristine. In theory, the very first stars in the universe would have been composed of pure hydrogen and helium, the first elements to emerge from the Big Bang.

Some of these galaxies were birthing stars at a prodigious rate, more than 10 times as fast as the Milky Way, which is 10 to 100 times as big. Others in the young group were barely generating one star a year, “which is an interesting diversity in a group of galaxies at this early epoch,” Dr. Morishita said.

All this adds to a suspicion among some cosmologists that the early universe was producing stars, galaxies and black holes much faster than the standard theory predicts. In an email, Dr. Morishita said there was not yet any “crisis” in cosmology.

“The easier explanation,” he wrote, “is that our prior understanding of star formation and dust production in the early universe, which are complex phenomena, was incomplete.”